Academic fraud undermines the integrity of education and research, shaking the foundation upon which knowledge is built. It encompasses a range of unethical behaviors by students, researchers, and educators that misrepresent the truth. This blog delves into the types of academic fraud, real-world case studies, and measures implemented to combat this issue.

Types of Academic

Fraud

· Plagiarism: The unauthorized use or close

imitation of the language and thoughts of another author without

acknowledgment. Plagiarism can occur in various forms, such as:

o

Direct Plagiarism: Copying another author's work

word-for-word without citation.

o

Self-Plagiarism: Reusing one's own previously

published work without acknowledgment, presenting it as new research.

o

Mosaic Plagiarism: Piecing together ideas,

phrases, and concepts from different sources without proper citation, creating

a patchwork of borrowed material.

o

Accidental Plagiarism: Unintentional failure to

cite sources correctly, often due to lack of knowledge about proper citation

practices.

·

Fabrication and Falsification: These are serious

offenses in the realm of research and academia.

o

Fabrication: Making up data, experiments, or

findings that were never conducted or observed. This includes creating

fictional research results and reporting them as real.

o

Falsification: Manipulating research data,

equipment, or processes to produce desired results. This can involve altering

data points, selectively reporting results, or modifying images in research

publications.

·

Cheating: Dishonest behavior in academic

assessments, encompassing various tactics used to gain unfair advantage.

· Ghostwriting: When someone writes work for

another person, who then submits it as their own. This practice is prevalent in

academic publishing and student assignments.

o Academic Papers: Scholars hiring ghostwriters to produce articles or research papers submitted for publication.

· Data Manipulation: Subtly altering research data

to achieve more favorable outcomes without outright fabrication or

falsification.

o

P-Hacking: Manipulating data analysis until

nonsignificant results become significant, often through selective reporting of

positive results.

o

Cherry-Picking: Only reporting data that

supports a desired hypothesis while ignoring data that contradicts it.

· Unethical Collaboration: Inappropriate or

dishonest collaboration between researchers, often to enhance the perceived

credibility or impact of their work.

o

Gift Authorship: Listing individuals as authors

who did not significantly contribute to the research, often to curry favor or

inflate the paper's credibility.

o

Salami Slicing: Splitting one significant piece

of research into several smaller publications to increase the number of

publications on a CV.

·

Misrepresentation of Sources: Citing sources

that were not actually used or misrepresenting the context of cited

information.

o

Fake Citations: Inventing sources or citing

nonexistent works to support research claims.

o

Distorted Citations: Misrepresenting the

conclusions or findings of a source to bolster one's own arguments.

Frauds done by Publishing House

Academic fraud is not limited to the actions of individuals;

publishing houses can also engage in unethical practices that undermine the

integrity of scholarly communication. Here, we explore various types of fraud

committed by publishing houses, illustrating the consequences of these actions

and the steps being taken to address them.

· Predatory publishing refers to exploitative

academic publishers that charge publication fees without providing legitimate

editorial and publishing services. Characteristics of predatory publishers

include:

o

Lack of Peer Review: Accepting and publishing

papers without rigorous peer review, thereby compromising the quality and

reliability of the research.

o

Aggressive Solicitation: Spamming researchers

with invitations to submit papers or join editorial boards, often with the

promise of rapid publication.

o Misleading Metrics: Using fake or misleading impact factors and other metrics to appear more credible

Citation manipulation involves practices that artificially inflate the citation metrics of a journal or specific articles. This can occur through:

o

Citation Cartels: Agreements between journals to

cite each other’s articles extensively to boost impact factors.

o

Coercive Citation: Editors pressuring authors to

add citations to articles from the editor’s journal that are not relevant to

the paper’s content.

·

Some publishing houses organize fake conferences

and launch bogus journals that exist solely to extract fees from researchers:

o

Fake Conferences: Hosting conferences with

little to no academic value, often accepting any submitted abstract or paper

for a fee.

o

Bogus Journals: Creating journals that mimic the

appearance of legitimate ones but lack rigorous editorial and peer review

processes.

·

Encouraging or allowing duplicate and redundant

publications dilutes the scientific literature and misrepresents the amount of

unique research:

o

Duplicate Publication: Publishing the same

research in multiple journals or conference proceedings without proper

cross-referencing or justification.

o

Redundant Publication: Splitting a single study

into several parts to increase the number of publications without significant

new information.

Case Studies of Publishing House Fraud

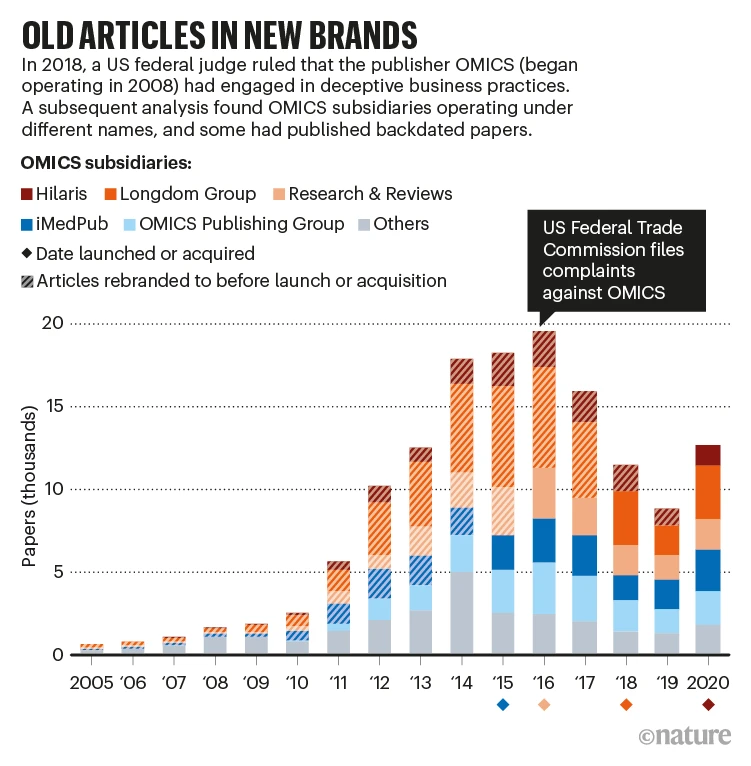

OMICS International, a publisher known for organizing

conferences and publishing journals, has faced criticism and legal action for

predatory practices. In 2019, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) won a

court case against OMICS, accusing it of deceiving researchers about the nature

of its peer review process and the true costs of publication.

In 2014, SAGE Publications retracted 60 articles from one of

its journals after discovering a peer review ring, where the same individuals

were reviewing each other's work without proper oversight. This incident

highlighted the vulnerabilities in peer review processes and the potential for

abuse.

In the mid-2000s, Elsevier faced a scandal when it was

revealed that it had published six fake journals sponsored by pharmaceutical

companies. These journals appeared to be legitimate, peer-reviewed scientific

journals but were, in fact, marketing tools for the companies' products.

Case Studies of Academic Fraud

The LaCour Scandal: In 2014, Michael LaCour, a

political science graduate student at UCLA, published a study in Science

claiming that gay canvassers could change people's views on same-sex marriage.

However, in 2015, it was revealed that LaCour had fabricated the data. His

co-author and the journal retracted the paper, and LaCour faced severe

professional consequences .

The Diederik Stapel Case: Diederik Stapel, a Dutch

social psychologist, fabricated data in dozens of research papers over several

years. His fraud was uncovered in 2011, leading to the retraction of over 50

papers and significant damage to his career and the credibility of social

psychology research.

Steps Taken to Combat Academic Fraud

1. Institutional

Policies

Many educational institutions have implemented strict

academic integrity policies. These policies outline the definitions of fraud,

the consequences of engaging in such behavior, and the processes for addressing

allegations. For example, Harvard University has an Honor Code that emphasizes

integrity and details procedures for handling violations .

2. Technological

Solutions

Software like Turnitin and Grammarly is widely used to

detect plagiarism in student submissions and scholarly works. Additionally,

digital tools for data verification and statistical analysis help identify

anomalies in research data, aiding in the detection of fabrication and

falsification .

3. Education and

Training

Institutions are increasingly focusing on educating students

and staff about academic integrity. Workshops, online courses, and orientation

programs aim to instill ethical research and academic practices from the outset

.

4. Regulatory Bodies

and Journals

Scientific journals and academic conferences are tightening

their peer review processes. Organizations like the Committee on Publication

Ethics (COPE) provide guidelines to maintain high ethical standards in

publishing. Journals are more vigilant in retracting fraudulent papers and

publicly addressing issues of misconduct .

5. Whistleblower

Protections

Encouraging the reporting of academic fraud is crucial. Many

institutions have established confidential channels for whistleblowers and

offer protections against retaliation. This ensures that individuals can report

unethical behavior without fear of negative repercussions .

Conclusion

Academic fraud is a multifaceted issue that threatens the

credibility and reliability of academic work. Through stringent policies,

technological advancements, educational efforts, and robust support for

whistleblowers, the academic community is actively combating fraud. Continued

vigilance and ethical commitment are essential to preserve the integrity of

academia.

References

1. Martin, B. (2013). Plagiarism: Policy against Fraud in

Student Work. University of Wollongong. https://policies.uow.edu.au/document/view-current.php?id=26

2. Office of Research Integrity. (2020). Fabrication and

Falsification. https://ori.hhs.gov/data-fabrication-and-falsification-how-avoid-detect-evaluate-and-report

3. ‘Teddi’ Fishman, T. (2016). Academic Integrity as an

Educational Concept, Concern, and Movement in US Institutions of Higher

Learning. In: Bretag, T. (eds) Handbook of Academic Integrity. Springer,

Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_1

4. COPE Council. (2019). Guidance for Editors: research,

audit and service evaluations. Guidance for Editors: research, audit and

service evaluations. https://doi.org/10.24318/B0fI5nuw

5. Turnitin. (2021). How Turnitin Works. https://www.turnitin.com/search/?query=how+Turnitin+works

6. Marcia McNutt, Editorial retraction. Science 351, 569 – 569

(2016). https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.351.6273.569-a

7. Levelt Committee, Noort Committee, & Drenth

Committee. (2012). Final Report: Flawed Science: The Fraudulent Research

Practices of Social Psychologist Diederik Stapel. Tilburg University. https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/sites/default/files/download/Final%20report%20Flawed%20Science_2.pdf

8. Carafoli, E. (2015). Scientific misconduct: the dark side

of science. Rendiconti Lincei, 26, 369-382. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12210-015-0415-4

9. Umlauf, M. G., & Mochizuki, Y. (2018). Predatory

publishing and cybercrime targeting academics. International Journal of Nursing

Practice, 24, e12656. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijn.12656

10. Paraskevopoulos, P., Boldrini, C., Passarella, A. et al.

The academic wanderer: structure of collaboration network and relation with

research performance. Appl Netw Sci 6, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-021-00369-4

16. Siler, K., Vincent-Lamarre, P., Sugimoto, C. R., &

Larivière, V. (2021). Predatory publishers’ latest scam: bootlegged and

rebranded papers. Nature, 598(7882), 563-565. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02906-8#:~:text=In%202018%2C%20the%20US%20Federal%20Trade%20Commission%20%28FTC%29,academic%20disciplines%20with%20little%20or%20no%20peer%20review.

17. Buranyi, S. (2017). Is the Staggeringly Profitable

Business of Scientific Publishing Bad for Science? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science

18. Van Noorden, R. (2023). More than 10,000 research papers

were retracted in 2023—a new record. Nature, 624(7992), 479-481. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03974-8

19. Grant, B. (2009). Elsevier Published 6 Fake Journals.

The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/elsevier-published-6-fake-journals-44160

True, plagiarism is a virus, which carries this fraud, people in order to become famous use this short cut, we have to cut short this virus to kill this fraud. Samidha has brought the impact of this virus into light with lucidity.

ReplyDelete